Gojira Productions, Inc. was registered by Chris Lee on July the 27th, 1994. Pre-production had begun and De Bont started by meeting Elliott and Rossio to brainstorm about the story. The script had already been revised, but De Bont wanted to bring his own touch. “De Bont was a great interpretive director,” said Rossio, “clarifying, emphasizing, making changes for momentum, adjustments for the intricacies of production and for budget. We had a great time” (Aiken, 2015).

De Bont also began hiring crewmembers, starting with long time collaborator Boyd Shermis as a visual effects supervisor. Initial tasks included storyboarding of major action sequences and subsequent breakdown into what special effects techniques would have to be employed – thus determining the film’s budget in that regard and hiring the needed number of effects companies) and production designer Joseph Nemec III.

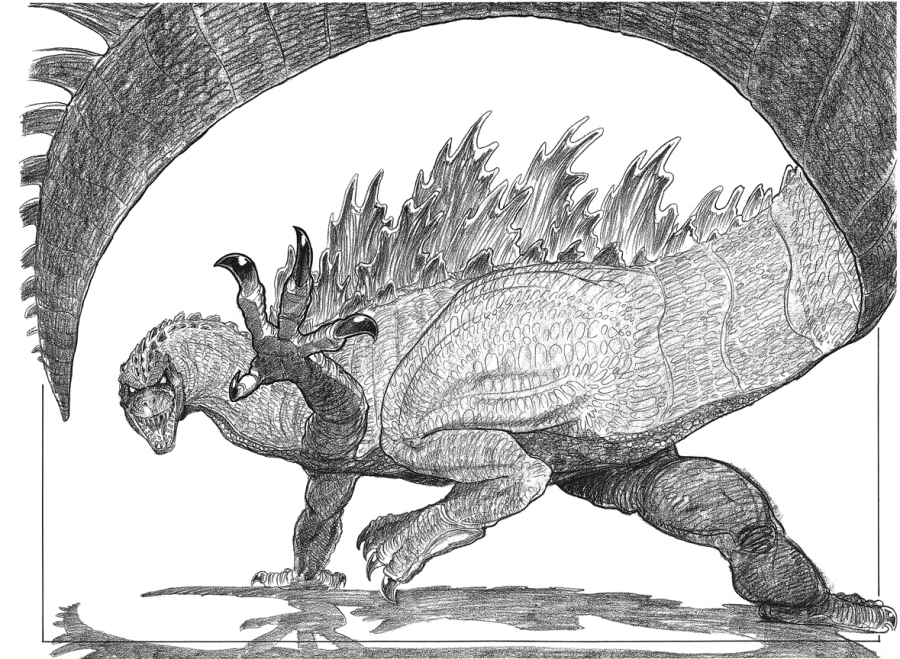

To bring the creatures of the project to life, De Bont met with Stan Winston Studio early on. Concept artist Mark ‘Crash’ McCreery was assigned creature designs, and started with a full illustration of Godzilla caught in a fight with the military. “One of my strong points in working with Stan was creating artwork that captured the essence of what they were hopefully looking for as far as the tone and attitudes towards the film,” McCreery recalled. “The first drawing that I did for Godzilla was kind of like that. It depicted Godzilla in a pose that was not reminiscent of the original at all; it was much more animated and animal-like and less human. It depicted some jets flying in and used under lighting which I always thought was classic Godzilla, him being so huge the lighting was always coming from underneath. So I retained as much of the classic look of Godzilla as I could, but I added some of my own — especially after working on Jurassic Park — dinosaur and character qualities.” McCreery’s artwork impressed De Bont since the beginning. “Crash… talk about artists! If you look at his archive, it deserves museum shows,” he commented (Aiken, 2015).

The director also assembled other concept artists to visualize Godzilla and the other creatures of the story. Among them was Ricardo Delgado, who immediately sought to collaborate on the project when he read about it. He explained: “I got into this project based a lot on my dinosaur comic, Age of Reptiles. I saw an article in The Hollywood Reporter that Jan was going to direct the movie and I had once interviewed with Jan to do storyboards for Speed. So I called his office, told them that I had done a dinosaur comic and faxed over some samples. Subsequently, I was invited to come to his production company, Blue Tulip Productions, on the Fox lot.”

Delgado prepared for the interview by drawing a few key illustrations. “I had just been so impressed with the Tyrannosaur in Jurassic Park — in all the dinosaurs in that film — and it was one of those things where I really felt that Godzilla needed that modern, textural interpretation of what a creature that size would be like in reality.” Delgado prepared for the interview by devising two Godzilla drawings – a pencil render and a colour illustration. Impressed by Delgado’s drawings – as well as his illustrations for the comic Age of Reptiles – De Bont and Nemec took him on board. Concurrently, concept artist Carlos Huante joined the project — specifically to design the alien creatures.

Winston Studio had not been given the bid at that point; all the involved artists were asked to work on the creature designs concurrently. Delgado explained: “we knew that Stan Winston was involved early on enough to have Crash McCreery generate a couple of images, but we were told to do our versions of the creatures.” By the time of Delgado and Huante’s involvement, McCreery had already produced key illustrations; Winston Studio’s work would never collide with that of other artists involved in the project (Aiken, 2015).

Storyboard work was commissioned to illustrators David Russell – who also did additional creature designs mentioned in the script – and Giacomo Ghiazza. Meanwhile, Delgado and Huante mostly collaborated with Joe Nemec. Early Godzilla designs by Delgado were more theropod-based, but Nemec pushed for something more conservative. Delgado recalled: “there were a few early drawings that I did more in the vein of crossing Godzilla with The Beast From 20.000 Fathoms because that’s kind of a fluid connection for me; it was natural to mix them together a little bit. The early ones felt more reptilian… I think I went through a few different drawings that felt very much like a dinosaur or the Beast with Godzilla fins stuck on the back. And Joe said, ‘that’s cool, but let’s push it a little more towards the Godzilla aspect of it’.”

Following this direction, Delgado began refining his concept art by referencing Toho’s Godzilla designs. “I had plenty of my own reference material because I was such a fan,” Delgado related. “I had Japanese Godzilla books and magazines that I looked at. I had a few of the Godzilla model kits made by Kaiyodo and Billiken, and those models from the early 90s were very helpful when I was designing the creature’s face.” Delgado also decided to distance himself from an overtly dinosaur-like Godzilla. “To me, some of the Japanese creature designs were based on calligraphic stuff I’ve seen of animals,” he explained. “For example, in King Kong Escapes, the Toho version of King Kong is almost based on the way calligraphy is done for apes or demons. That’s how I felt Godzilla was depicted a little bit, with some of the facial stuff around the cheeks and toward the snout, and the way the snout was separated into three pieces in front of the nose and on each side of the cheek. So I was really careful in analyzing that, and very reverential. I really respected the Toho design. Taking my ego out of it, I really wanted this Godzilla to be a combination of my meager contribution and Toho’s Godzilla. If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”

Delgado’s designs were finalized as three key illustrations drawn and submitted in September 1994. “It had the ponderousness and muscularity of Godzilla but I didn’t want the ‘thunder thighs’ Godzilla; I felt it still needed to make biological sense without really beefing up the legs too much. There’s a paddle of a tail that feels a little more crocodilian. But the head, the torso… perhaps it’s a little thinner, more muscular than the traditional Godzilla, but if you look at it in silhouette you’d go ‘that’s Godzilla’. You really need to look at the curve of the head, and the way it holds its arms in front of its chest, and the way the spines go back gracefully. And ultimately I really felt that, in those last three sketches, that it all came together to make it feel like Godzilla. I wanted to hit a home run with my design and say ‘That’s the Toho Godzilla with a dash of dinosaur put into it’. And that’s really all that it needed to be.”

Delgado’s designs were ideal for the goal of an agile Godzilla — something inspired by Jurassic Park — as opposed to the incarnations seen up until that point. Delgado elaborated: “you would feel its weight moving around, but when it had to move for the story it could actually move very quickly. A lot of modern reptiles – like Komodo dragons and crocodiles – they look like they’re really slow and ponderous creatures but if they want to come and get you they’re going to come and get you. They’re capable of sudden bursts of speed. That was one of the surprises that I was hoping would be part of the story – that in every way, shape and form he would be the Godzilla from the original films in the way he moved, but he would be capable of these quick bursts of speed. It would walk like a traditional Godzilla, he would lumber a lot, but then Godzilla would surprise you with this ability. And when it had to run forward – and that’s how I drew it, running forward – the tail would come up. But otherwise, its tail would drag just like the Godzilla we saw in our childhoods.” In addition, Godzilla could move on all fours – like a traditional reptile – when the situation called for it (Aiken, 2015).

No less effort went into designing Godzilla’s foe, the Gryphon. As far as De Bont was concerned, Godzilla needed an imposing adversary to fight. “You have to have a second monster because Godzilla can’t be the bad guy,” he claimed. “Godzilla in itself means nothing if there isn’t an opponent that threatens him.”

Based on the descriptions provided in the screenplay, Huante attempted to craft an organic creature design. “To be honest, the description for the Gryphon was cartoony, so for me the challenge was to try and make it all real,” he said. “My approach was to find unique silhouettes that encase beautiful forms. I remember that I stared at pictures of animals. Like I said, I just wanted the thing to look real, which wasn’t easy given the description.”

Delgado and Huante also began working on creature maquettes – but before those could be finished, news came in: in October 1994, Winston Studio’s bid to design and build the creature effects was officialized. “Stan had a contractual agreement to design Godzilla,” Delgado explained, “and it wasn’t until he was officially on the show that they told us, ‘hey, we’re going with Stan’. And you know, I’m just a kid and Stan’s won multiple Oscars and he’s got a huge crew. Carlos and I were told that our services were being shifted over. After that, I believe we did some production drawings not related to the creatures.” Delgado and Huante’s work would be left completely unused.

Winston Studio would thus be principally be involved in the creature design process, and also supply maquettes for digital scans, as well as mechanical puppets and creature suits. Effects director Boyd Shermis believed that those would be kept to a bare minimum – and that the film would mainly rely on digital effects to portray its monsters. He recalled: “Jan and I both wanted to keep Stan Winston Studio’s involvement to a bare minimum. We both believed in the CGI and neither of us were happy to see ‘puppets’ be used. Godzilla was just too huge as a creature to go with animatronics.”

De Bont added: “we were going to do some animatronics. For some of the facial things, we were thinking about building just the head to control some of the motions even more smoothly; and we definitely had some of Stan’s artists working on it and they came up with some ideas. The question was the scale of it… they had never worked on such a big scale and that’s always a little bit problematic. The bigger the creature is, the harder it is to make it move in an organic way, as if it has life. It was going to be a combination of quite a few different things. It would have been better than a fully CGI movie because, if you use animatronics and film it right and find the right filming speed, it can be very dramatic. It’s hard to do those things because you don’t know what you can do with the animatronics and what motions you can make until you actually have the machine working. So we were never thinking about doing the whole creature. It was always going to be the head, the claws… sections for when we had to get closer in and make it look more real. I don’t recall the exact scale, but it would look real.”

The process started with McCreery’s Godzilla renderings.“Stan really liked to leave his mark,” the artist said, “it was his signature – so he would let us go off, do our own thing, and develop it in-house without the influence of anything else that had been done before so that he could really call it his own. He had a lot of pride in our work and his work in that manner. It wasn’t that he was keeping it from us for any reason other than just wanting us to be free to do what it is we love to do.” McCreery wanted to retain several key traits of the character, saying that “there were a lot of characteristics about the original Godzilla that, unless you retain them, it’s really not that character anymore.”

Toho’s first Godzilla had been designed under two main influences: artistic depictions of Japanese demons and dragons, and life restorations of dinosaurs of the time. In particular, Godzilla borrowed elements from illustrations of Tyrannosaurus (for the general silhouette) and Stegosaurus (the plates lining its neck and back) [REFINE] (Ryfle, 1999). Until the 80s, the general consensus held that bipedal dinosaurs walked upright; Godzilla’s traditional posture was based on this theory. From the 60s onwards, skeletal and biomechanical analyses eventually revealed that bipedal dinosaurs walked with their bodies parallel to the ground – a revolution in dinosaur life restorations.

Despite the advancement in scientific knowledge, McCreery felt that the erect posture was a key trait to maintain when redesigning Godzilla. He said: “standing very upright, which is a very Charles Knight, old school way of thinking about dinosaurs where the legs and torso are more upright – which made total sense since it was a guy in a suit in the original – trying to make that feel real and natural was really difficult.” Generally speaking, keeping the original silhouette was an imperative: “Godzilla has such an iconic silhouette, it was real important for us to try and maintain it,” said McCreery. “Other iterations since have been great endeavors and certainly have qualities of their own that I’ve always been impressed by, but I’ve never felt like it was the Godzilla we’ve all grown up to know and love. But that’s what’s great about filmmaking; it’s always interpretations, a director’s vision or a producer’s vision. That’s what makes it interesting. And that’s what makes ours special, too. That was its own idea of how you could redo Godzilla. There’s a lot of different ways you could redo it.” Essentially, the major design work went towards updating the textures of Godzilla, endowing it with realistic scales and other details based on real reptiles – such as crocodiles and monitor lizards – and giving it dinosaur-like qualities. Godzilla’s iconic skin texture had been based on the keloid scars found in survivors of atomic bombings; with the atomic connection removed and the intention to make Godzilla look more realistic, its textures could also change.

McCreery continues: “I wanted to give it a scaly texture, a lizard texture. And also enhance the dorsal fins; make them feel more bone-like, some kind of real world texture that you can relate to. Maintaining the silhouette was important; whenever you see those fins you know who that is. Godzilla’s skin texture was always kind of odd to me. It was always very nondescript, more of a texture without referencing any kind of animal. I tried to make sense of that texture on Godzilla. I also added a contrast between its belly and its back, just to give it a little more interest. And more detail in the head; again, trying to make it feel a little more naturalistic.”

Joey Orosco – assisted by Scott Stoddard, David Monzingo, Mike Smithson, and Paul Mejias – was assigned the task to translate McCreery’s drawings into a three-dimensional maquette of Godzilla, interpreting the concepts in the process to make them function properly in three dimensions. “Any change that Joey’s ever made, I’ve always looked at as being an improvement,” McCreery commented. “Joey’s sculpting always took what worked from my designs and then whatever worked from his point of view and style, and integrated that as well; and it always seemed to develop into its own thing, a little bit of everybody, which is cool.”

In sculpting the maquette, Orosco also referenced the proportions of the Toho Godzilla designs. He recalled: “We had photo blowups of the original Godzilla and we wanted to make sure the tail length compared to the body on the maquette was really close to what it was [on the original Toho creature]; and with a lot of lizards and komodo dragons the tails are almost longer than the torso, so you have to nail that and make sure the tail is very, very long for balance.” The full maquette portrayed Godzilla in a neutral position with an open mouth; a Godzilla bust (with its mouth closed) was also sculpted by Joey Orosco and Mark Maitre.

Maitre, along with Stoddard, Monzingo, and Jim Charmatz, was also responsible for the Gryphon maquette, again based on McCreery designs. The Probe Bats were instead designed and sculpted into a maquette by Bruce Spaulding Fuller.

The entire design process had to advance at a quick pace. De Bont explained: “the reason it had to be fast was that they were trying to find out, early on, what could be achieved with using Winston’s animatronics company. We were trying to figure out what would be the most effective and economical. CGI was getting there but it wasn’t perfect; it was still being fine-tuned. And CGI shots in those days were really expensive… people tend to forget that now. Especially if you wanted to do those shots in 4K, it was almost twice as much work because it had to be so perfect.”

On the visual effects side, Godzilla was certainly an ambitious project: not only De Bont wanted digital creatures, but also wholly digital environments. Boyd Shermis estimated – after the initial visual effects breakdown – that the film would need over 500 visual effects shots. Where modern blockbusters exceed such number by far, for the 90s it was an unprecedented amount of digital effects sequences. In addition, the visual effects crew would also have to research and develop new softwares for the kinds of effects and simulations that had to be portrayed in the film. As a result, TriStar pushed the start of production back to early 1995 (Aiken, 2015).

Industrial Light & Magic – the effects wizards behind Jurassic Park – was an obvious first choice, but turned the project down due to large scheduling conflicts. Impressed with the compositing effects seen in the music video for the song Love is Strong by The Rolling Stones, De Bont sought the collaboration of those responsible: the crew at Digital Domain. Interestingly, Digital Domain had been co-founded by Stan Winston – together with James Cameron and Scott Ross, former Senior Vice President at LucasArts. Digital Domain officially joined the project in October 1994 and was given six months to develop the new needed software to successfully create the effects De Bont wanted.

Work was split with two other companies – Sony Pictures Imageworks and VIFX – which would be supervised by Digital Domain. Imageworks had been working for the project for a long time, and even before De Bont – and his crew – had been hired, the company had produced the first digital creature test for the film – creating a digital model based on maquettes supplied by Jeff Farley and John Hood. Said footage has never been released in any form.

Godzilla was about to become a showcase of groundbreaking digital effects; and one of the innovative aspects was that De Bont intended to use motion capture to animate Godzilla – homaging the traditional means of a creature suit used to bring the character to life up until that point. “The motions a person can make that you transfer to a creature, it gives the creature a little bit of heart and soul,” De Bont said. He also added: “The men in the suit have some very endearing qualities that you kind of lose with CGI. In that regard, when people are using actors to play the monster and then later translate the actor’s feelings to the monster you have a much better chance of doing that; and that’s what we kind of planned as well. We were doing some tests for motion-capture, and we talked to many people about the best way to do that. At the time, it was very effective, actually… like in the silent movie period, actors would have to tell a story with the movement of their arms and facial expressions, and people understood the story. Godzilla can’t talk either — he can scream, he can roar — therefore, the idea that an actor can portray that and then transfer that performance to the creature via motion-capture would be very, very beneficial and effective.” (Aiken, 2015).

The film would also need its fair share of effects that did not involve creatures. For the extensive miniatures that had to be built for certain sequences, Stetson Visual Services, Inc. was approached – but the project’s cancellation was officialized before any work could be done. On the other hand, large sets were being constructed when that notice came in. Fxperts inc., led by John Frazier, was hired for the film’s full-size practical effects – including pyrotechnics, cars, and sets. In November 1994, Frazier and crew went to to Lone Ranch Beach in Brookings, Oregon to start building a full scale Japanese fishing village, which would be featured in one of the film’s early scenes. The finished set would have included include structures that would collapse simulating Godzilla crushing them under its feet.

As the various elements of pre-production proceeded, De Bont also started assembling a cast of actors for the film. Contrary to early TriStar reports that Godzilla would sport A-list actors, De Bont believed that since Godzilla was the real focus, the film did not need big stars. “It’s one of those things where, as a director, you hope so much that you get a screenplay that is really fantastic, that doesn’t need any stars to make it work,” the director said. “Godzilla is the star… that is what we always said. We didn’t need anybody outdoing him.”

De Bont’s favoured choices for the main characters were Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton – a duo that would eventually star in Twister (1996). “I couldn’t really offer Godzilla to them because the picture wasn’t green lighted yet, but I had them in mind,” De Bont said. With everything falling into place, De Bont planned to start filming in March 1995 (Aiken, 2015), but the efforts done up to that point were about to be undone.

Financial and managerial issues at Sony Pictures had begun far before pre-production on Godzilla had started. In September 1989, Sony Corporation bought Columbia Pictures and its sister company, TriStar Pictures, from the Coca-Cola Company for a sum of $3.4 billion, with an additional $1.5 billion to cover long-term debt at the two studios. Peter Guber and his producing partner Jon Peters were chosen to run the new studio. To get the two producers, Sony had to acquire the failing Guber-Peters Entertainment – for $200 million – and also had to pay $700 million to buy out Guber and Peters’ contract with Warner Bros. In turn, Guber and Peters engaged their lawyer Alan Levine to be the chief operating officer and president of Filmed Entertainment Group – which included Columbia, TriStar and other divisions – which would become eventually known as Sony Pictures Entertainment by 1991. The deal with Warner Bros. Involved the trading of a MGM studio lot in Culver City in exchange for Columbia Pictures’ 35% share of Warner’s Burbank Studios. As part of a consolidating process for all of its divisions in Culver City, Sony Pictures reportedly spent $130-150 million to transform the old studio into a state-of-the-art facility. In addition, Guber and Peters also used the company’s money for their own – and costly – personal expenses. Ironically, Peters was forced out of Sony by Guber in 1991.

Production-wise, the situation became ambiguous in the following years: on one hand, under Guber, certain films – such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula – gained high commercial success, allowing Sony to surpass many rivals; on the other, Sony was also hurt by box-office flops like Last Action Hero. By the midst of 1994, Sony’s movie divisions had a debt of around $250 million, with a 10% drop in market share. The company attempted to sell off a quarter stake in the studio for $3 billion, with scarce success. Rumors began to spread around Hollywood that Sony Corporation had something under the carpet – either shut down Sony Pictures or fire all the studio executives, including Guber (Aiken, 2015). Sensing the danger, the producer resigned on September 29, 1994 (taking from Sony $40 million plus the agreed $275 million to launch Mandalay Entertainment Group).

In a flurry of financial losses – including $520 million in unfinished projects – Sony Pictures’ studio executives became progressively afraid of making new films – one wrong step and for all they knew they could be fired at any given time. According to journalist Peter Bart, “the decision-makers at Sony were essentially looking for excuses not to make movies” (Bart, 1999).

It did not take long for this extremely negative buzz to reach De Bont and his crew. The production department at TriStar had estimated a $140-$180 million to effectively create the film as De Bont intended it, and Sony at the time was not willing to spend more than $100 million on it. In addition, the studio executives foresaw additional costs. “Everything was being looked at in a micro way,” Cary Woods related, “and with a $140 million budget for a movie with this many effects, everybody tacks on another 30%. So the studio was looking at a movie they thought was going to be $200 million” (Nashawaty, 1998).

Rossio added: “I recall the line producer taking a page from our script, holding it up and saying, ‘this is a six million dollar page.’ It was a section of the final battle between Godzilla and the Gryphon, in and around the World Trade Centers in New York. At the time we were oddly proud of having written a six million dollar page!” The writer, however, understood the concerns regarding costs, saying that “the budget issues were totally realistic. Remember, this was just as CGI was emerging as a viable technology. I think Jurassic Park has something like twelve minutes, total – largely due to the expense. We wrote an epic Godzilla story.”

In a recent interview with SciFi Japan, De Bont offered a different viewpoint on the matter, claiming that Sony was pushing for an ‘Americanized’ Godzilla. “They were extremely worried that the American audience wouldn’t go for Godzilla,” he related. “I said, ‘I think they won’t go for it if you Americanize it. That would be the worst thing you can do to Godzilla’. Godzilla doesn’t warrant that, it doesn’t need that. To get a great audience you have to get people to like him and appreciate what he’s all about. And what they wanted to do almost immediately was change the story… have more fights, more characters that have nothing to do with Godzilla, big fights with other creatures” (Aiken, 2015).

Throughout November to December 1994, De Bont attempted to nail down a compromise with the producers, all during pre-production of the project. Among the attempts to convince executives that the project could still be viable was a display of maquettes and concept art that had been created up to that point, but to no avail. Elliott and Rossio also submitted their final revision of the script on December 9, 1994. At the same time, the director, along with producer Barrie Osborne and production designer Joseph Nemec reconfigured the budget into a sum of $100 million. “We could show on paper how it could be done for that amount,” De Bont said. “CGI at the time was pretty new but I have a lot of experience with effects — more than most directors — and I know how to get them done and make them more original.”

Despite the efforts, De Bont’s offer was rejected by Sony. However, the company wanted to keep the director on board and in mid-December they approached the director with yet another pitch: to lower the budget of the film, the Gryphon would have to be completely excised from the story. De Bont adamantly objected the idea: “they don’t realize that if you take something out you have to replace it with something else at least as good or the movie’s too short and the story development of Godzilla is completely useless. It’s gone, and the story just jumps from scene to scene with no point.”

Ironically – shortly afterwards – the studio had another proposal that was projected to save expenses for a film series. Rossio explained: “Sony made a request at one point that we create a sidekick, a Robin-type monster to Godzilla’s Batman. Ironic, at the same time the studio was coming to the decision they couldn’t afford a monster for Godzilla to fight, they were asking us to add another monster character. The studio didn’t have sequel rights, so they wanted us to create a ‘helper’ monster for Godzilla they could spin off and serialize. Yes, they were hoping to make a Godzilla sequel without Godzilla.” De Bont added: “it was an absurd suggestion, of course. It would have been like Batman and Robin but you cannot have two equally important characters in a movie like this. To me, it was much more important to have a worthy opponent.” The director felt that the idea of a sidekick “goes against the origin of Godzilla. He’s a unique creature; he’s a loner so the more of a supporting cast he has, the less important he is. I think that goes against the power of the character.”The major creative differences, budget conflicts and somewhat ambiguous studio intentions put a strain on the director. With the back-and-forth negotiations continuing to no avail, De Bont ultimately left Godzilla on December 26, 1994. “It’s not so much that I left it,” De Bont stated. “They basically let me go. They used the argument that ‘we want another director who can do it cheaper and faster’. These were the two arguments that were used, and none of them are true. I think they wanted a director that they could tell more what to do.” De Bont took no time in moving on – and signed to direct Twister a month later in January 1995.

Winston Studio was still working on the creature designs when De Bont’s Godzilla was cancelled. “The creature designs were still evolving. Those were definitely not the final ones,” the director said (Aiken, 2015). Interestingly, some of the Winston Studio crew — like Mark Maitre — also worked on Roland Emmerich’s version.

Following De Bont’s departure, Godzilla collapsed – with its production shut down by the studio. “It was a big crew, and [Sony] let us all go and they said they were going to redevelop it,” De Bont said (Aiken, 2015).

Next>>